The run-off of the presidential elections turned into a big occasion of celebration for the pro-reform electorate at home and in the diaspora. The leader of the opposition, former Prime Minister Maia Sandu, won the election, gaining almost 1 million votes out of 1.6 million votes cast.

Moldova has a new President: strong popular vote for a “weak” political institution

Diaspora against Dodon

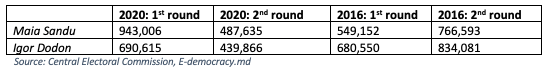

The outcome of the elections was inspiring in many regards. The two candidates incentivized citizens to vote more actively than four years ago. Maia Sandu obtained almost 58% of the total votes, compared to less-successful candidate Igor Dodon’s 42%. Her results improved by approximately 200,000 votes from the second round of the 2016 presidential elections that she lost against Igor Dodon. The overall turnout improved by 4% – 52.7% compared to 48.5% in the first round (See Table 1).

Table 1. Primary data from the 2020 Moldovan elections

One of the turning points in the second round was Dodon’s statement that the diaspora would represent the country’s “parallel electorate.” These mistakes, made by his electoral advisers, enraged voters abroad, who increased their turnout in the run-off by 57%. Consequently, both diaspora and migrants constituted about 16% (around 262,000) of the total voters. Their vote went to Sandu at a proportion of almost 93%. At some polling stations –Frankfurt, London, etc. – voting ballots ran out, leaving hundreds of voters without the possibility to cast their vote.

The various electoral techniques and means used by Dodon to offset the vote of the irritated diaspora did not pay off.

First of all, the mobilization of the voters who live in the country’s Transnistrian region was short-lived. Though they doubled their presence, reaching 31,000 voters, it was not enough to balance out the diaspora. Moreover, the involvement of Transnistria’s electorate came along with incompliance with electoral legislation, which prohibits organized transportation and criminalizes vote-buying.

Secondly, the accentuation of aggressive discourse, including personal attacks against Maia Sandu, had a smaller impact than expected on undecided voters, who supported other candidates in the first round. Perhaps under normal conditions, a negatively-fueled campaign would have yielded different results. However, amid the pandemic, public perception has experienced shifts in priorities. That aspect was miscalculated by Dodon’s team, which explains why he was only able to increase his votes by about 250,000, compared to the almost half million more obtained by Sandu in the run-off. In this regard, Igor Dodon scored less than in 2016 by about 143,000 votes, while Maia Sandu received about 176,000 votes more (See Table 2).

Table 2. The number of votes for Maia Sandu and Igor Dodon in the 2020 and 2016 presidential elections

Finally, the conditions in which the elections took place were better than in previous electoral cycles. Correspondingly, Maia Sandu had higher chances of winning the elections. The OSCE indicated that electoral rules were largely respected. Nevertheless, several previously visible shortcomings, such as intolerant discourse, party financing, or disproportionate media coverage, were still observed. Even the harshly criticized Central Electoral Commission (CEC) made several changes that created exceptions from the relatively strict electoral legislation. Restrictions were adopted for the transportation of voters who live in Transnistria, reducing the number of permitted passengers to a maximum of 8 per vehicle. This was not enough to avoid irregularities once and for all. However, this complicated attempts at vote-buying and transportation of this category of voters. Another example of the CEC’s adaptability was the extension of the time allowed for voting at external polling stations, making it possible for queueing diaspora to vote in the first round.

Nevertheless, Sandu’s team and her supporters expressed condemnation with regard to police inaction or the CEC’s lack of imagination with regard to policy to increase the number of voting ballots abroad. Despite this criticism, it is fair to acknowledge that the authorities acted within existing electoral law. The latter entails various inconsistencies and lapses that should be effectively addressed to perfect future electoral exercises. One of the major breakthroughs for elections that would benefit the diaspora would be mail or absentee voting, which neighboring Romania already implements.

Geopolitics were used in the elections, but in subtle ways

Both candidates engaged with geopolitics during the campaign, though the modalities differed. They, however, did not operate with geopolitical discourse as a primary one. The external preferences of voters became more symbolical and tougher to grasp, but remained powerful. That touches upon the values and the ethos of the voters. Consequently, the rule of law, symbolizing European aspirations, countered the discourses about the traditional family or the narrative about “Western external agents”.

On one hand, Sandu has always been aware that the diaspora is voting, discretely, from a geopolitical perspective. A significant share of Moldovans from Italy, Germany, and France, or even from the post-Brexit UK have a clear sense of geopolitical belonging to particular values that characterize their hosting countries in Europe. They have chosen to migrate to the West, not to Russia, because they prefer good governance, which also implies the rule of law and better economic opportunities. Their lives in Europe and on the other side of the Atlantic reflect the opposite of what exists in Moldova and Russia. The latter is still on the list of destinations of Moldovan migrants, but Russia’s attractiveness is worsening in terms of economic benefits and labor standards. Official Russian statistics estimated that the share of Moldovan workers dropped in 2018 compared to 2017 by 16%, reducing the number to about 357,000 people. Similarly, 2019 remittances from Russia reached a level of USD 21.9 million (2 times more than from Italy), which is 4% fewer than in 2018. That is indicative of the phenomenon of the shrinking Moldovan contingent of workers in Russia. It undermines Russian geopolitical influence over the Moldovan voters, who are increasingly opting for EU countries.

On the other hand, Igor Dodon tried to pedal the geopolitical discourse referring to other values than the rule of law, driven by the pro-Western platform. He attempted to remind voters that he is a proponent of traditional values, gravitating around family and the church. To sharpen his point, Dodon referred to speculations around Sandu’s position toward the LGBT community, exploiting the fact that his opponent does not have a family or children. Another way to introduce geopolitics was by intoxicating the public with the false ideas that Sandu would endeavor to liquidate Moldovan statehood in favor of territorial reunification with Romania. Last but not least, Dodon’s campaign encapsulated some hints of conspiracies about “colored revolutions” exported by the West, and the domination of local civil society by George Soros. Some Russian-speaking media from Moldova supported these type of conspiracies, even Russia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Serghey Lavrov and President Vladimir Putin himself. They tried to draw parallels with ongoing political events in Belarus and Kyrgyzstan.

So, geopolitics were not absent from these elections, but took a more invisible and subtle form through a dynamic electoral conversation about values. The candidates were less interested in exploiting geopolitics in a more tangible manner. Therefore, the idea of multi-vector politics appeared prominent in the electoral programs of both Igor Dodon and Maia Sandu. The latter even started to employ Russian language more frequently,and interact with Russian-speaking foreign journalists ahead of the run-off. Thanks to that, she managed to discourage suspicions and speculations about her anti-Russian position.

Domestic politics – not “a perfect storm”

The existing configuration in the parliament and executive branch does not serve Sandu’s plans to implement immediate radical changes. She has to confront a parliament without a majority and a government that was appointed by Dodon. That limits her maneuverability considerably at the beginning of her mandate. Positive and negative scenarios can both emerge out of the lack of ability to leverage power.

On a positive note, Sandu has a real chance to create a more transparent and politically responsible presidency. One of the measures she claimed immediately after entering office was to slash the presidential budget. These kind of populist measures can buy her time until she can set up a working relationship with the legislature. Ideally, she will need a comfortable parliamentary majority, led by her party, the Action and Solidarity Party. With that in hand, president-elect Sandu can dismiss the government and appoint a new cabinet of ministers.

Unfavorable scenarios will unfold against Sandu’s strategic goals if she fails to build strong alliances within the existing parliament, regardless of its compromised legitimacy. In early 2019, the oligarchic regime designed a suitable electoral system seeking to perpetuate control over institutions. Consequently, many elected parliamentarians have since represented the interests of oligarchic groups, while the opposition weakened. To dissolve the parliament, Sandu requires a majority in the parliament, even if just a technical one, and the right timing with regard to when to stage an interruption of the parliament’s mandate. Without that, she cannot do much to change the status quo substantially. Under these circumstances from the president’s office, she may face the constraints of making bold statements, rather than actually effectively influencing policy-making domestically.

New foreign policy is inevitable

Maia Sandu as president convinced voters and external partners about a “correctly” balanced foreign policy,which would entail mending dialog with Romania and Ukraine. Contrary to the way it was portrayed by Sandu and her political party, Moldova was not isolated from its neighboring countries. On the contrary, relations with these countries developed in various fields, from energy security to trade and cross-border cooperation. However, a more accurate assessment would show that a certain degree of frosty relations persisted only at the level of their presidential offices. The reluctance toward Dodon derived from his numerous attempts to please the Kremlin publicly.

The EU and central EU member states, such as Germany, will become a priority for Sandu’s presidency. She has the intention to bring in more financial aid and investments from them, and relies significantly on Western support to help the country overcome the economic consequences of the sanitary crisis. To do that, she will need to ensure that the parliament and executive branch implement the conditionality principle, meaning an efficient flow of reforms. Having no say over these two institutions may underscore her impotence as president, underlining the objective limitations of presidential powers.

The real complications in foreign policy will be in the form of dialog with Russia, which should be carefully adjusted, avoiding unnecessary turbulence. In general, Russian authorities dislike politicians within the CIS space that act independently. During Dodon’s entire mandate, the Moldovan presidency was a strong ally of Russian interests in the region. With Sandu taking over the office, past loyalty toward Moscow will drop to zero very quickly, which is one the reasons she was supported by voters – to strengthen the country’s sovereignty and national security.

Conclusion

Maia Sandu’s victory has already created a boost of high expectations from her mandate. To succeed, she should communicate sincerely about the constraints of her office from day one. Maintaining high expectations without delivering may harm her image and the political capital of her party. Strategic and sincere communication inside and outside her office will give her more credit rather than show weakness. At the same time, president-elect Sandu has to be strategic and fight the political battles that matter most instead of clashing with parliament or the government over less critical issues. It is futile to overlook the weakness of the presidency and only focus on the robust popular vote that put a pro-reformist in the position of becoming the country’s president.