This article raises the awareness for current and future strategic threats to the security of critical energy transport and energy infrastructure. At the moment, NATO’s operational readiness centres around the “Single fuel policy”, which is based on fossil kerosene. At the Madrid NATO summit in 2020 the Alliance announced its goal to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050. The resulting transition to renewable energy will bring new challenges to the armed forces of the Alliance. The energy systems will become more diverse and complex and thus will create more vulnerabilities. All these changes require an increased focus on all aspects of energy security and critical energy infrastructure protection.

Vulnerabilities of the global energy system

Modern societies depend on huge amounts of energy. Since WW II, the global fossil energy consumption has risen seven-fold to 136 TWh (2021). Most energy is still provided as fossil- based oil and gas while electricity from renewable sources contributes 8 TWh.[1] Within NATO countries, most energy related infrastructure is owned and managed by public or private civil entities. Only minor components like the Central European Pipeline System are controlled by NATO armed forces.

Most NATO countries are not energy self-sufficient and therefore vulnerable to changes in the political alliances of the producers.

Transporting and transforming fuels from the source to the customer is a multinational effort. Most NATO countries are not energy self-sufficient and therefore vulnerable to changes in the political alliances of the producers. Processing plants are located in both, producing and consuming countries, typically close to seaports. Rotterdam harbour in the Netherlands for example hosts five oil refineries covering large areas and therefore are easy and vulnerable targets for kinetic attacks (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Large oil refinery and storage facilities in the seaport of Rotterdam[2]

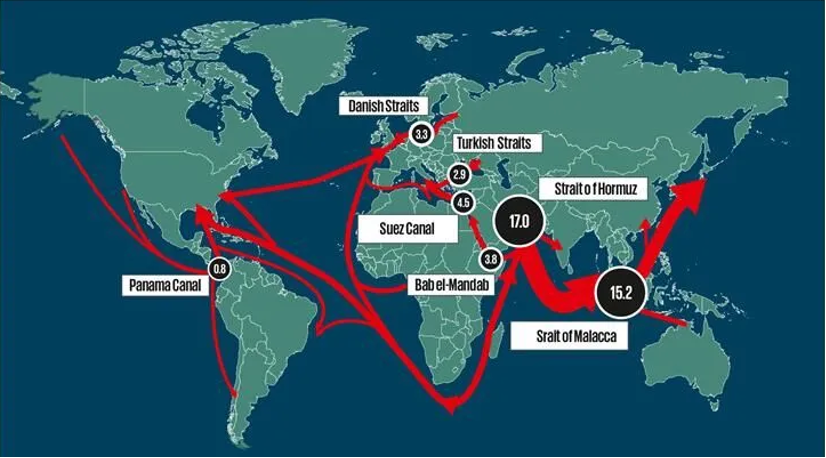

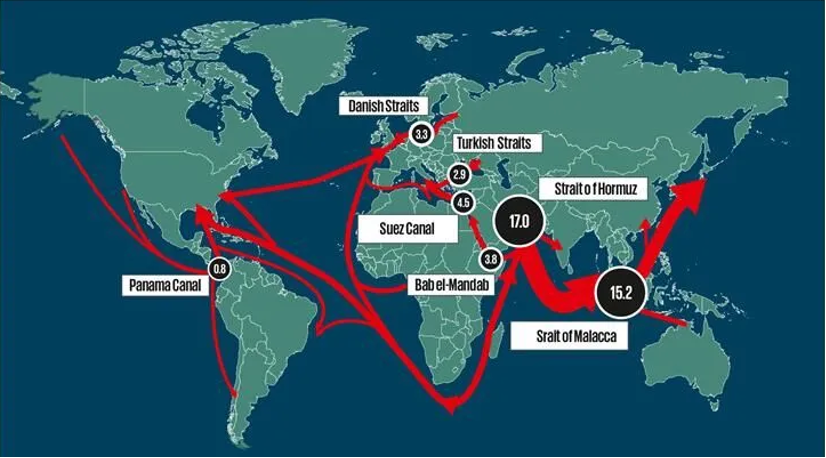

Globally, 63 % of fossil oil (Figure 2)[3] and 10 % of natural gas[4] are transported by ship and therefore prone to obstructions at maritime bottlenecks. Recent examples are the six-day blockage of the Suez Canal in 2021 (daily throughput 4.5 million barrels of oil), piracy in the Strait of Malaga (15.2 million barrels per day) or military interventions in the Strait of Hurmuz (17.0 million barrels per day). Such incidents threaten the global energy supply chain. In contrast, long distance transport on land is usually performed via pipelines (Figure 4). Only for the “last mile”, trains and trucks are used. Recent cyber- or kinetic sabotages on refineries and pipelines demonstrated the vulnerability of these installations and logistic hubs.

Figure 2: Transport routes and bottlenecks for fossil oil shipping. The numbers indicate the estimated oil volumes in million barrels per day. (1 million barrels equals 1,628 GWh[5]).

Facing climatic changes, industrial societies are now making strong efforts to de-fossilize their energy supply by switching to electricity generated from renewable sources. Critical infrastructure for electricity production are power plants, transformer stations and electrical grids. Power plants using fossil fuel, nuclear, hydropower or geothermal sources are compact facilities. In contrast, solar- and wind parks (c.f. Figure 3, a solar power plant in Chile) as well as the power transmission grid cover large areas and are difficult to protect against kinetic attacks. This became evident during the Russian-Ukrainian war. Because electric power loss can cause a nuclear meltdown in nuclear plants, the International Atomic Energy Agency is currently warning of this serious threat at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant on the Russian-Ukraine frontline.

Transitions are generally difficult processes. Success, hick-ups and failures are close. Some of the main challenges to NATO are discussed next.

Figure 3: Large photo-voltaic power plant in Chile[6].

Strategic challenges related to NATO and its single fuel policy

For NATO members and partner countries, the current energy challenges are very complex and securing energy availability is essential. In the current international efforts of a transition away from fossil to renewable energy production, industrial societies with limited fossil energy resources are facing a dilemma: They need to invest enormous financial resources for building a renewable energy supply chain based on carbon neutral electric power production while at the same time competing on the global markets with societies which continue to use fossil fuels.

The technological progress in using electricity for airplanes, ships and heavy land-based systems like trucks and armoured systems is physically limited and propulsion systems using liquid hydrocarbon-based fuels simply perform superior.

The technological progress in using electricity for airplanes, ships and heavy land-based systems like trucks and armoured systems is physically limited and propulsion systems using liquid hydrocarbon-based fuels simply perform superior. Consequently, the military and many civil transport systems will depend for the next decades on hydrocarbon-based liquid fuels. An environmentally sound “way out” would be using renewable electric energy for the production of carbon neutral synthetic fuel by combining carbon capture and hydrolysis. However, this is energetically less efficient and therefore expensive[7]. To keep up in combat effectiveness with potential adversaries who are using fossil fuels, NATO armed forces are forced to either continue using fossil fuels or acquire expensive synthetic fuels.

NATO armed forces are adhering to the NATO single fuel policy, which aims to use one globally available primary fuel type. Currently, this is kerosene jet fuel, the mainstay of civil air transport. Efforts are underway to replace it by sustainable air fuels, which are blends of kerosene with up to 50% bio-, or synthetic fuels. The geo-strategic challenges for securing fossil energy supply are well known. The build-up of additional renewable energy and electricity-based production facilities and infrastructure needed for large quantities of synthetic hydrocarbon-based fuels pose challenges of almost epic dimensions. Not only does this require huge investments, the total amount of electricity needed from renewable sources can realistically not be produced within most NATO countries. This will create new global markets for renewable energy production and shift the focus towards countries within the global solar belt. Consequently, NATO countries will have to exchange some strategic dependencies from fossil producers with dependencies from global renewable energy providers. This also means that such new energy and transport infrastructures have to be protected to ensure energy security.

New supply chains must be built up while the old ones are still operated. The increased complexity requires agile management and vigilance to establish resilient structures and protocols since their effectiveness can only be evaluated in hindsight after disruptive events. NATO armed forces depend primarily on civil society energy supply chains. Therefore, protective measures for energy installations and systems must include private, national and military infrastructure protection and security protocols.

Protecting energy systems

Energy systems are very complex and may fail in unpredictable ways. The complexity and sheer size of the global oil and natural gas shipping ways and pipelines (c.f. Figure 2 and Figure 4) is a challenge in itself. Operating it requires a multitude of technologies and procedures with thousands of human, physical and virtual interfaces are very difficult to protect from hostile forces even in peace times. Any concerted kinetic and cyber-attack within an economic zone or synchronized electric power grid has the potential to knock out civil and military activities. The establishment of additional infrastructure as “shock absorber” on all levels of operations and supply chains is essential to augment energy security. These measures will increase costs and can only be enforced within a state or supranational structure.

An increasingly electrified world will add new challenges to the protection of the energy supply. Electricity must be produced instantly and in exactly the amount, it is needed. Therefore, any incapacitated electrical infrastructure, until the last demand point, must be repaired before electric energy can be provided again. This poses serious risks, as large-scale electricity storage technology is not yet available. The bifurcation in the energy mix by having fossil and alternative fuels during the next decades will add even more diverse and additional infrastructures and increase the number of potential targets.

Additionally, agile risk management must anticipate any “blind spots” as hostile forces will certainly do so.

All challenges discussed must be addressed in the next decades, because the change to a de-fossilized energy future will be a long process. Additionally, agile risk management must anticipate any “blind spots” as hostile forces will certainly do so.

Figure 4: Map of the extensive global natural gas pipeline network.[8]

Conclusions

Failing to ensure a secure environment for a stable and reliable supply of energy to population, industry and defense forces, means to fail as a state. For NATO nations and partners, this has to be avoided by any means. This statement remains valid for civil governments and for military commanders, for a single Nation and for the entire Alliance. What matters most is the security and stability of the complex energy environment starting from energy production and conversion all the way to distribution and consumption by civil society and the armed forces. In this context, the choice of energy sources – renewable or not – is of secondary nature.

The demands of today’s civil society and armed forces for ensuring energy security is more than understandable, given the current global conflicts and the technological transition to a non-fossil and zero-carbon energy world. NATO must convey and shape the message that energy is no longer an easy to obtain commodity for our Nations and that armed forces will not be able to exclude themselves from this vision. Since energy security is essential, the mission of critical energy infrastructure protection cannot be ignored or outsourced in the future.

While currently most NATO armed forces are not directly assigned to critical energy infrastructure protection on their own soil, it is now time to accept the challenge and to rapidly adapt to the mission because military and national security depends on these assets. Energy Security is a global challenge that can only be managed through a collective and comprehensive conceptual framework of efforts and mitigations. Realistic resilience concepts must start by realizing how vulnerable we are and be followed by a comprehensive risk assessment. Only those overarching efforts will lead NATO successfully through the energy transition and ensure the security of the Alliance.