This analytical review aims to provide a fine-grained assessment of the evolution of Sino–Lithuanian bilateral relations since the opening of the Taiwanese Representative Office Vilnius, which resulted in an all-out conflict. The article argues that since the China–Lithuania spat began, hardly any aspect of their bilateral ties has been left unaffected. Therefore, the analysis is divided into the economic, diplomatic, and informational spheres to assess the changes that occurred since the relations started deteriorating two years ago. Along with a narrower focus on bilateral ties, the paper also provides an assessment of how Lithuania’s approach can be seen within the broader context of the EU’s ties with China and de-risking measures.

Sino-Lithuanian Relationship: Cautious Engagement, Ties and its Impact on the EU De-Risking Policy

1. ECONOMIC FRONTLINE

Following the opening of a Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius in November 2021, Lithuania has received a bouquet of China’s novel economic coercion measures. Instead of straightforwardly imposing a customs block on Lithuanian exports, China has adopted rather covert tactics such as promptly eliminating the very name of the country from the customs system. Therefore, having faced an intense episode of Chinese covert economic coercion, and being mindful of China’s increasing economic and geopolitical clout, Lithuania has had to intensify efforts to securitize its economy by introducing a slew of legislative amendments in 2022 and further fostering its economic diversification policy.

Lithuania’s safeguards

Lithuania has, first, strengthened its foreign investment screening mechanism by adopting an updated version of the original 2002 Law on the Protection of Objects Critical for National Security in 2022. One of the noteworthy amendments of the law has been that enterprises critical for national security must now “notify of their intention to conclude transactions”, instead of notifying of the “transactions intended to be concluded”. Such a notification of intent would seemingly compel enterprises to be more cautious and vigilant when developing business ties, whether those would be with China or any other hostile country, thus avoiding any undesirable outcomes.

Concurrently, in 2022, Lithuania adopted legislation to ensure that only equipment from trusted manufacturers is used in critical infrastructure, including 5G infrastructure. Amendments to the Law on Public Procurement, the Law on the Procurement by Contracting Authorities Operating in the Water, Energy, Transport and Postal Services Sectors, and the Law on Procurement in the Field of Defence and Security of the Republic of Lithuania were adopted to manage the risks to national security arising from the use of unreliable information technology in critical infrastructure. While the amendments are not formally targeting China, it does have a China angle. After all, in 2021 Lithuania blocked the controversial company Nuctech from installing its equipment in the country’s critical infrastructure, and banned Chinese telecommunications vendor Huawei from developing a local 5G network, thus addressing the threats associated with dependence on China’s technological solutions.

Besides their proactivity on the legislative front, Lithuania has also been remarkably consistent with its aim of strategic diversification, which was presented in the centre-right government’s official program in 2020. The progress towards this aim was indeed accelerated by the punitive brunt of China’s coercive actions coupled with the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and the resulting economic fallout for European countries dependent on energy supplies from Russia. Against this backdrop, Lithuania has rolled up its sleeves to diversify away from reliance on China and other unstable markets, and has thus pivoted to the Indo-Pacific region. Notably, in the first half of 2022, exports of Lithuanian-origin goods to the ten Indo-Pacific countries increased by 60.4%, exceeding the volume of exports to China fourfold, thus not only diversifying trade but also increasing economic resilience by reducing economic dependence on China. The pledges of strategic diversification have also been reinforced in the Indo-Pacific Strategy published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) on July 5th, 2023. The new document has called for “developing economic cooperation with countries in the region in a mutually beneficial manner to achieve the objectives of strategic diversification”.

Lithuania as a “China-free” Country? The Reality of Sino–Lithuanian Economic Engagement

On the surface, it would seem that Lithuania’s efforts to securitize its economy would further inform its dealings with China, that is, putting any interactions with China under scrutiny, thus cautiously engaging with it at minimum, or, at maximum, adopting a steer-clear approach. The latter option would entail avoiding China altogether and becoming a “China-free” country, which is perceived to be “an advantage” by Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis. However, the developments in 2023 on the economic frontline unveil a different reality, and the realization of a “China-free” country is just wishful thinking.

What stands out first, is that Lithuania has seen an increase in China’s investment inflows into the country. Curiously, until the crisis, China was a minuscule source of foreign direct investment in Lithuania. In fact, Lithuania’s own investment into China was eight times larger in 2020: €157 million against €18.3 million (source: Official Statistics Portal). Therefore, considering this negligible investment from China, the prevailing notion among the senior officials in Vilnius was that Lithuania has little to lose from the crisis, in full throttle calling “big China small”.

However, these recent investment dynamics seem to have started to reverse, with China slowly but steadily increasing its investments in Lithuania. Indeed, the signs of Lithuania slowly opening the doors to Chinese investments have started to manifest already in 2021, with China investing about €130 million, rising to €176.5 million in 2022, and already reaching €128.7 million in the first half of 2023, which is nearly 8 times more than Lithuanian investments into China, €16.2 million – a reversal of the 2020 dynamics. The available data from the Official Statistics Portal’s indicates that the primary Chinese investment magnet is aimed at manufacturing – in particular transport equipment manufacturing – followed by administrative and support service activities, wholesale and retail trade, and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles.

Figure 1: Inward and outward foreign direct investment in the first half of 2023. Source: Official Statistics Portal.

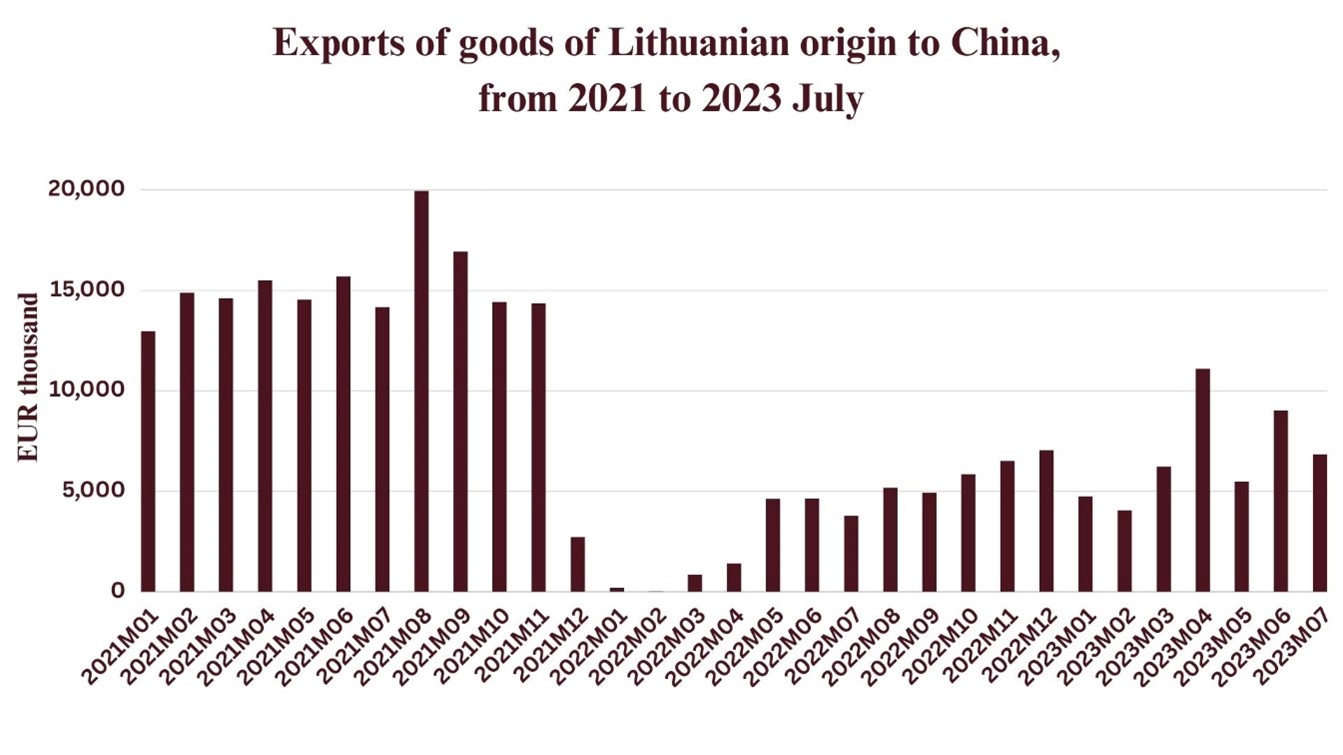

As for trade, both sides have softened their stances toward each other. Lithuania exported goods worth €208.1 million to China in 2019, €243.9 million in 2020 and €170.8 million in 2021. In 2022, trade with China declined to €45.2 million after China imposed primary sanctions on Lithuania. Based on the latest figures, however, it seems that Lithuania has weathered China’s wrath. In the first half of this year, €40.7 million worth of Lithuanian-origin goods was exported to the country, which already almost amounts to the total amount of 2022. The main driver of the increase was the export of mineral products, followed by the exports of miscellaneous manufactured articles. However, observing the prospects of further movement of exports, the status quo ante volume is hard to imagine as there is still a significant decline. Moreover, Lithuania’s Economy and Innovation Ministry has downplayed the importance of re-entering the Chinese market, noting that “exports to China are likely to grow, but will not become a priority export market. Companies are in no hurry to renew existing trade relations and exports to China are subject to political risks.” With that being said, Lithuania’s exports are set to operate in a neutral gear without any additional state-led efforts to re-enter the Chinese market.

Figure 2: Exports of goods of Lithuanian origin to China, from 2021 to 2023 July. Source: Official Statistics Portal.

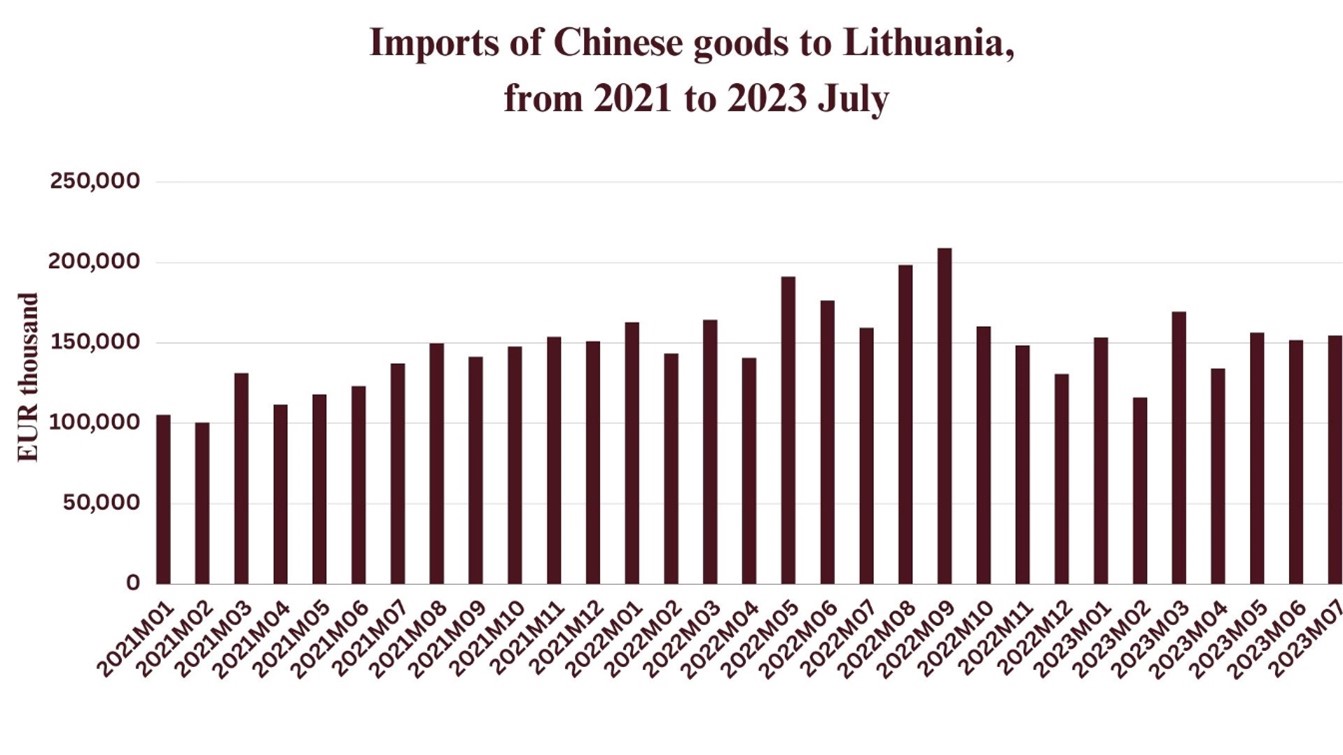

Furthermore, the wishful vision for a ‘China-free’ country can be easily trampled when imports are taken into consideration. When the crisis between Lithuania and China was flourishing, Lithuania recorded a dramatic rise in imports from China, with 2022 being the record year with almost $2 billion worth of goods coming from China. Economists tied last year’s record imports from China to the good performance of Lithuania’s retail industry coupled with China’s reopening after the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a shortened delivery time and ‘back to normal’ logistics. Curiously, Lithuania seems to be on a similar track this year as well, reaching €881.6 million by July, which is already nearly half of 2022. As in 2022 and before, the main drivers of imports remained the same: electrical machinery and equipment and parts thereof, sound recorders and reproducers, television image and sound recorders, as well as nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery, and mechanical appliances and parts thereof.

Figure 3: Imports of Chinese goods to Lithuania, from 2021 to 2023 July. Source: Official Statistics Portal.

In sum, the overview of Lithuania’s economic interactions with China provides a check-in with reality. That is to say, it is a test whether Lithuania’s preventive campaign against dependence on China has translated into an avoidance of China altogether, and thus becoming, as Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis put, a “China-free” country. But as data reveals, to become free from China, or, as now popularly touted, to completely decouple from China, is impossible for Lithuania. Undoubtedly, China’s economic whiplash has left lasting scars, and so a return to pre-crisis levels in economic relations with China is still hardly imaginable.

2. DIPLOMATIC FRONTLINE

Contrary to the cautious but more positive economic engagement, Lithuania has been locked into a standstill in its diplomatic ties with China, with still no tangible progress in mending them.

First, China continues to maintain its unilaterally imposed decision of downgrading its diplomatic relations with Lithuania to the chargé d’affaires level, which is the lowest level of diplomatic engagement according to the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. It is noteworthy, however, that the office of the chargé d’affaires of China in Lithuania still provides consular services, and so China’s diplomatic mission appears to maintain some of its basic functions. Secondly, China’s potentially newly appointed chargé d’affaires’ previous diplomatic activity also provides a hint at what China sees as the greatest obstacle in bilateral ties. Huang Xuehu, who appears to be the new chargé d’affaires to Lithuania from September 2023, has previously worked as a counsellor at the Chinese embassy in Fiji from around 2018 to 2019. Moreover, Huang has also worked as a counsellor at the Chinese embassy in Kiribati from around 2020 to 2022. These latest diplomatic appointments indeed entail a symbolic meaning – Huang coming to Lithuania right after Fiji and Kiribati signals that China does not prioritize Lithuania in its diplomatic agenda. Even though the first impression can be that China has randomly appointed a diplomat to Lithuania with no experience in EU-related affairs, what is more interesting, yet overlooked, is that Huang has experience working against the increasing influence of Taiwan in third countries: both Fiji and Kiribati have long been and still remain an important stage for a fierce fight between China and Taiwan over influence in these countries. With that being said, the second impression that can be drawn is that China is tactically sending a diplomat who is experienced in curbing one more disobedient country when it comes to Taiwan.

Figure 4: Huang Xuehu delivers a speech during the 74th Anniversary of the Founding of the PRC in Vilnius. Source: Xinhuanet.

When Chinese officials’ rhetoric is also considered, only a low ceiling can be set when it comes to how much progress is possible in reinvigorating diplomatic relations. When several Lithuanian parliamentarians, including the chairman of the Committee on National Security and Defence, visited Taiwan and met President Tsai Ing-wen at the beginning of the year, China slammed the visit and accused Lithuania of “violating its commitment made upon the establishment of diplomatic ties with China”, and urged to “return to the one-China principle as soon as possible”. A similar rhetorical pattern – that Lithuania does not live up to its political commitment to the one-China policy – has also penetrated China’s reaction toward the Indo-Pacific Strategy. In the strategy, Lithuania claims that it is “seeking to enhance practical cooperation with Taiwan” and that “the development of economic relations with Taiwan is one of Lithuania’s strategic priorities”. This statement has undoubtedly been sensitively received by China, which not only denounced Lithuania once again for violating its political commitment to the one-China principle but also accused Lithuania of cooperating with the US in the all-around encirclement of China, as if Lithuania would be a US pawn in containing China. The same belligerent tone seems to continue to linger with no prospects of vanishing when former Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė’s visit to Taiwan on August 22 is considered as well. China unsurprisingly condemned the visit as “wrongful acts that run counter to the one-China principle” and “gross interference in China’s internal affairs”.

Taken as a whole, it seems that China sees Lithuania as the only actor responsible for adding fuel to the already intensively flaming diplomatic relationship. From China’s perspective, Lithuania continues to intentionally poke at China’s sensitive point, Taiwan, with which Lithuania has been actively expanding cooperation. This has resulted in Lithuania being considered to have the most pro-Taiwanese stance in the EU. However, what is noteworthy is that Lithuania’s approach to the extent it can cooperate with Taiwan is cautious and measured. This can be illustrated by Lithuania’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Gabrielius Landsbergis’ avoidance of meeting Taiwan’s foreign minister, Joseph Wu, during his most recent diplomatic tour of the three Baltic States. This avoidance implies that Lithuania, despite being a staunch Taiwan supporter, does not want to infuriate Beijing and inflame its grievances that it is hollowing out its one-China policy. Therefore, this might potentially send signals to Beijing that Lithuania is willing to normalize their diplomatic relations, even though for now it remains at a standstill.

3. INFORMATIONAL FRONTLINE

The capacity to ‘control minds’ in the international arena is an important part of authoritarian countries’ arsenal of power. In the case of China, the build-up of external propaganda abilities gained much more prominence since Xi Jinping came to power. In 2013, within the first year of his tenure, Xi, attending the National Propaganda and Ideology Work Conference, famously said that “it is necessary to carefully carry out external propaganda work and create innovative external publicity methods”, and that all government apparatus must “properly tell the China story and spread the Chinese voice”. Since then, striving for huàyǔ quán (“话语权”, often translated as “discourse power”, but more accurately defined as “the right to speak”) in the international sphere has become deeply embedded into CCP’s main narrative. Therefore, it can be argued that China is more than ever active in the informational sphere, and most present in countries that are more vulnerable to a wide range of Chinese tools or those that have societies with more favourable or divided views on China.

However, within the regional context, Lithuania’s case is rather unique. Since the beginning of the deterioration of China–Lithuania relations, China’s already minimal digital influence in the country has reached new lows. In the 2022 report, published by the Centre for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), Lithuania is regarded as the country with the “lowest influence level across the region”, as the bilateral diplomatic conflict has resulted in a drastic reduction of China’s involvement in the country to “almost non-existent levels”. This is further confirmed by Lithuania’s 2023 National Threat Assessment which, contrary to the case of Russia, did not identify China’s informational influence as posing or having the potential to pose a threat to the country.

In 2023, the US Department of State published a report titled How the People’s Republic of China Seeks to Reshape the Global Information Environment that discusses Chinese measures for building its informational influencing capabilities in other countries.

| 1. Expansion of state-owned media |

| 2. Direct purchase of foreign media outlets |

| 3. Publishing PRC-made content in foreign media outlets (content-sharing agreements) |

| 4. Enhancing PRC diplomats’ media engagement |

| 5. Promotion of partnership networks |

| 6. Sponsorship of online influencers |

| 7. Laundering official commentary (false authorship) |

| 8. Manipulative social media tactics |

| 9. Monitoring communications |

| 10. Online and real-world intimidation |

| 11. Diplomatic pressure (media and academic institutions) |

Figure 5: Chinese means of influence. Source: US Department of State Global Engagement Center’s Report.

Chinese success stories in building its influence in foreign countries’ domestic media are unevenly spread across the world, with more significant gains in Southeast Asia. (Xinhua News agency’s print bureaus and CGTN Television operate in all 10 ASEAN countries.) In the Central and Eastern European region, the case of the Czech Republic can be seen as an example of China’s active push towards building influence in the domestic media. In 2015, China’s energy conglomerate CEFC acquired a controlling stake in the Czech Republic’s Empresa Media, which, according to CEPA’s report, resulted in a change from a more balanced to wholly positive coverage of China-related news.

In contrast, Lithuania is quite the exception in the region. Out of all the indicated measures (ref. Fig. 1), only No. 4 and No. 11 can be more relevant, albeit on a small scale. China has not acquired any stake in the country’s media agencies, and so the influence to adjust China-related coverage is extremely limited. The main public communication is done through Chinese diplomats who have maintained a very low profile since the diplomatic conflict. On rare occasions, paid op-eds written by the top Chinese diplomat (chargé d’affaires) in Lithuania can be found in the Lithuanian language newspaper Lietuvos Rytas (only in printed format). This year only two op-eds were published in said newspaper (April 20 and June 16).

Figure 6: Op-ed by China’s charge d’affairs in Lithuania, Qu Baihua, published in “Lietuvos Rytas” (15 June 2023). Source: Office of the Charge d’Affaires of the PRC in Lithuania.

Currently, the Chinese chargé d’affaires Bureau in Lithuania is exceedingly passive when it comes to public communication. The official website is rarely updated, with only occasional responses to Lithuania’s China-related remarks or decisions by the Bureau’s spokesperson. More interestingly, events organized by the Bureau are also kept ‘underground’. The most recent example – the official reception commemorating the 74th Anniversary of the PRC, which was held on 27 September – was only mentioned in Chinese domestic media (covered by the main state media outlet Xinhua and widely republished by various smaller agencies). The rationale behind such low-key communication is related to the current political animosity between China and Lithuania and the relative sensitivity of PRC-related information in the country.

China’s passiveness in the informational sphere is, to a large extent, based on the relative difficulty of spreading Chinese narratives in the country. According to the GLOBSEC Trends 2023 report, a survey conducted in Lithuania has indicated that Lithuanian society has developed a strong resilience to geopolitical disinformation. Responses to China-related questions position Lithuania as having one of the most negative views of China as a security threat, and only 10% of respondents hold a favourable opinion of Chinese President Xi. This further confirms that Lithuanian society is rather resilient to Chinese discourse.

The change in domestic coverage

Lithuania’s decision to quit the ‘17+1’ format and its plans to allow Taiwan to open its representative office in 2021 resulted in significant anti-Lithuanian rhetoric in the domestic media, with disinformation campaigns questioning Lithuania’s decision, sovereignty, and links with the US. The triggers of domestic media ‘fury’ often revolved around Taiwan-related news, Lithuania’s remarks and decisions regarding China, and China-related communication by Lithuanian officials on the international stage.

However, the situation has noticeably changed in 2023. It seems that the previously sensitive triggers, especially concerning Taiwan-related news, are instead toned down or, in some cases, completely ignored. While Lithuania still occasionally appears in the Chinese domestic media, the coverage has become more balanced and not overly negative (and, in some cases, filled with excitement as seen in the coverage after Lithuania’s national basketball team beat the US). This year, an exception to this indifference regarding political topics would be the Vilnius NATO Summit which, along with the release of Lithuania’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, has once again sparked anti-Lithuanian rhetoric. (Related commentary can be found in the previous EESC publication.)

Figure 7: The news headline “Lithuanian Taiichi Enthusiasts: Overcoming Difficulties to Practice Chinese Taiichi”. Recently, similar non-political coverage has become more prominent in the Chinese media while political topics are no longer overemphasized. Source: Xinhua News.

4. LITHUANIA’S DE-RISKING APPROACH FROM THE EU’S PERSPECTIVE

In the EU member states, the debates on China have not only intensified but have also significantly deepened in the last decade. As Bartsch and Wessling have noted, a majority of EU countries are now pursuing “more strategic approaches to China”. This trend is also reflected, albeit at a slower pace, in discussions of the EU’s approach to future relations with China, especially from the lenses of trade, investment, and technology securitization. In this regard, Lithuania’s reshaped approach to relations with China has had, to a certain extent, bloc-wide consequences.

In the wake of coercive and often covert Chinese actions, Lithuania, being a member of the European Union, has received support from the EU. Most importantly, the bloc, on behalf of Lithuania, has launched a dispute settlement case against China at the World Trade Organization (WTO). While it is widely expected that the WTO case will drag on for a long time, some progress is being made. On 20 December 2022, the first EU request to establish a formal panel (which would signal that the parties failed to solve the dispute bilaterally) was blocked by China which stated that it “held consultations with the EU in good faith and continued to engage with the EU after the consultations with a view to exploring the possibility of resolving the dispute in an amicable way”, and that China “believes it is premature to establish a panel in this dispute”. However, on 27 January 2023, the WTO members finally agreed to establish a dispute panel to examine Chinese coercive measures against Lithuania, with China stating that “it will vigorously defend its measures in the panel proceedings”.

While Lithuania’s unexpected conflict with China might have taken the EU by surprise, the overall trajectory of the EU’s trade policies and greater focus on security seems to be increasingly synchronized with Lithuania’s. Recent EU policy initiatives show that this trend is in unison with the Lithuanian government’s emphasis on a need for a tougher and more multi-layered approach in which economic pragmatism does not dominate the normative considerations.

| Foreign Direct Investment Screening Regulation

(effective since 11 October 2020) |

Goal: “to make sure that the EU is better equipped to identify, assess and mitigate potential risks for security or public order while remaining among the world’s most open investment areas.” |

| International Procurement Instrument

(effective since 29 August 2022) |

Goal: to increase EU leverage by allowing member states to ban products and firms from a country without reciprocal de jure access to its public procurement. |

| Foreign Subsidies Regulation

(effective since 12 July 2023) |

Goal: to tackle distorted foreign subsidies to ensure an equal footing for all companies operating in the EU market. |

| Anti-forced Labour instrument

(under negotiations since 12 September 2022) |

Goal: to ban all imports and exports connected with human rights abuses along with the creation of a risk-based approach to identifying sectors for investigation. |

| Critical Raw Materials Act

(under negotiations since 16 March 2023) |

Goal: to ensure EU access to a critical raw materials supply that is secure and sustainable, in accordance with its 2030 climate objectives. |

| European Chips Act

(effective since 21 September 2023) |

Goal: to increase the EU’s competitiveness and resilience in semiconductor technologies and applications, in order to assist in achieving both the digital and green transition. |

| European Economic Security Strategy

(under negotiations since 20 June 2023) |

Goal: to create a framework for achieving economic security by promoting the EU’s economic base and competitiveness; protecting against risks; and partnering with the broadest possible range of countries to address shared concerns and interests. |

| Anti-Coercion Instrument

(passed on 3 October 2023) |

Goal: to counter the use of economic coercion by non-EU countries. This legal instrument is in response to the EU and its Member States becoming the target of deliberate economic pressure in recent years. |

Figure 8: The latest measures that have a Chinese angle. Source: European Commission, European Parliament

As seen in Figure 8, the EU has recently launched and developed several instruments and regulations which do not explicitly refer to China but are without a doubt aimed at improving capabilities to deal with China’s increasing economic and geopolitical influence. Among those measures, the recently passed anti-coercion instrument is closely related to the Sino–Lithuanian conflict, as its relevance and depth of discussions were significantly boosted after China’s coercive measures against an EU member. According to the European Parliament, the anti-coercion instrument is “the EU’s new tool to fight economic threats and unfair trade restrictions by non-EU countries”. In the official statement, the main background that resulted in the need to develop such an economic instrument is said to be “economic pressure exerted by the US during the Trump administration, along with numerous confrontations between the EU and China”. Therefore, it can be argued that the adoption of such an instrument is closely related to Chinese actions against Lithuania.

De-risking rather than de-coupling?

The EU’s current China policy is guided by the “EU-China Strategic Outlook” that was reviewed in 2019. However, recent events – such as a resolution passed by the European Parliament concerning Hong Kong’s shrinking rights to free speech, and a draft report by the European Parliament’s Committee on Foreign Affairs concerning China–EU relations – reflect the transformative nature of bilateral ties towards a more structured approach with more concrete boundaries, especially when it comes to human rights and China’s use of leverage against EU members. Therefore, at the moment, the dynamics of EU–China relations resemble a rollercoaster ride in which there are significantly more downward slopes. While the EU is beginning to flex its muscles to set new game rules for cooperating with China, attempts to maintain a healthy engagement, especially in the economic sphere, are complicated and on shaky grounds.In 2022, China’s trade set a new record, albeit unfavourable for the bloc: the trade deficit with China reached 395.7 billion euros due to a continued increase in imports from China. Investment dynamics are also shaky: Rhodium Group reported that Chinese investment in the EU (including the UK) continues its multi-year decline.

The Chinese FDI in Europe reached a decade-low of just EUR 7.9 billion in 2022, down 22% compared to 2021 (or back to the 2013 level). While the long-awaited Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between China and the EU is now dead, re-engagement is proving to be not that easy. In addition to this, EU businesses in China are continuing to struggle in the domestic market with an uncertain future, even after the end of COVID-era restrictions. On 20 September, the European Chamber of Commerce in China published their “European Business in China Position Paper 2023/2024”, highlighting “how contradictory messaging from authorities over the past year has European businesses wondering what kind of relationship China wants to have with them”. The position paper not only identifies the challenges of doing business in China but also offers suggestions for the government to solve them. As stated by Jens Eskelund, president of the European Chamber, “our members want to increase their engagement and make bigger contributions to China’s development, but they now need to see concrete action being taken”. On September 23, 2023, during the visit to China, the European Commission’s Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis called for the resumption of dialogues and improved market access to have a “level playing field”. The re-engagement and some signs of enthusiasm from both sides are evident, but the unresolved and emerging problems (on 4 October, the European Commission formally launched an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese electric vehicles sold in the bloc) are still not addressed and, as a result, any real progress is hindered.

CONCLUSION: TOWARDS SUSTAINABILITY IN THE SINO–LITHUANIAN TIES?

Two years have passed since the opening of the Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius and the boiling point of the Sino–Lithuanian conflict that followed. On the surface, Lithuania’s rather firm stance and resistance amidst an authoritarian country’s pressure and qualitatively novel economic statecraft can be treated as a success story, in which it managed to emerge rather unscathed while also helping others realize that China is willing to use all leverages at its disposal to punish. The bilateral standoff has attracted the world’s attention. As a result, the EU provided support to Lithuania against China’s covert economic pressure.

In this tense situation, Lithuania proceeded with its diversification to the broader Indo-Pacific region, in which closer ties with Taiwan are also beginning to return some dividends. However, the dream of becoming a ‘China-free’ country that can completely decouple from the world’s second-largest economy might prove to be unrealistic: both on the economic and diplomatic fronts, Lithuania is moving further away from any decoupling.The small country, whose Foreign Minister was famously once described as a “dragon slayer”, seems to be softening its stance toward China and increasingly falls in line with the more cautious mainstream Western de-risking approach. Currently, Vilnius’ rhetoric in the international arena remains relatively more radical in its calls to decouple from China. Lithuania also remains one of the most important Taiwan supporters in the region – a stance that has also become more cautious, but the future of Taiwanese Representative Office is more or less unquestionable even in case of victory by the opposition parties in 2024 parliamentary elections. Lithuania’s precedent and position have become rather side-lined in the EU and US, who are emphasizing de-risking and, simultaneously, constructive multidimensional engagement with China, albeit with more caution and less focus on maximization of economic gains.Recently, China seems to have lost interest in Lithuania and is increasingly showing indifference.

This evolution in its approach is understandable: initially, Beijing feared that Vilnius’ precedent might lead to a domino effect in the region and, therefore, significantly affect the long-standing status quo. However, recent developments have made China realize that it might just be a ‘one-man show’ and Lithuania’s case is just an exception with no contagious effect. Admittedly, the remaining Baltic States – Latvia and Estonia – seem to have followed Lithuania’s decision to withdraw from the China–CEE cooperation format ‘16+1’. However, this happened a year later (at a time when the format was already ‘in a coma’ to say the least), which was arguably a calculated low-cost diplomatic move ‘to make a point’.The new unfolding geopolitical realities and tectonic shifts call for a strategic and sustainable approach toward China. Lithuania is likely to adopt a flexible and cautious mainstream de-risking approach that can also be values-based. It is difficult to comprehend how not having a functioning diplomatic representation with one of the world’s superpowers can be in the small state’s interests. Therefore, Vilnius is already showing intentions to normalize relations with Beijing, while also maintaining the already-established ties with Taipei. In this regard, Lithuania should avoid a zero-sum game, make a clear distinction between its approach to China and Taiwan, and strategically engage with both.